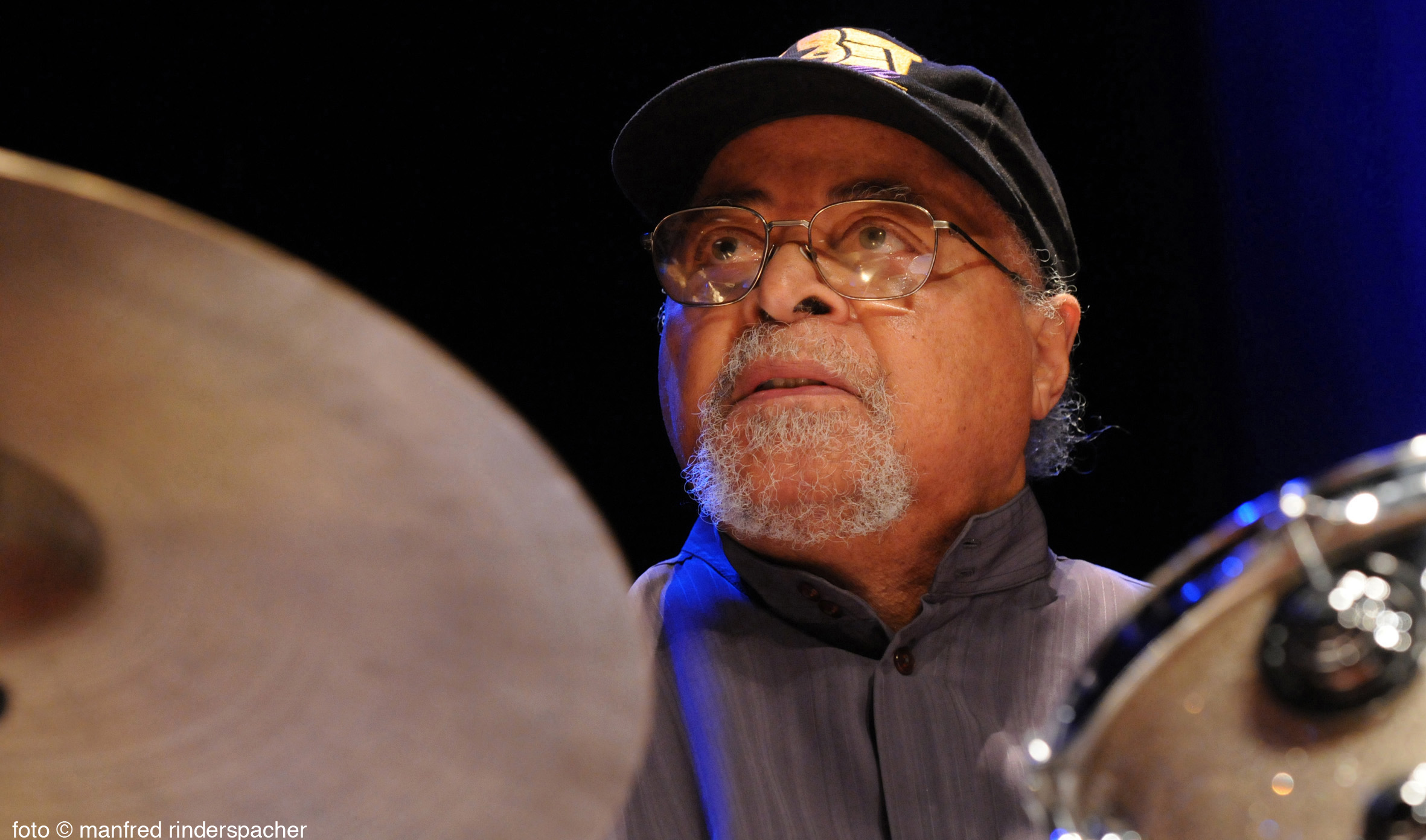

Sometimes all it takes is one performance to earn your place in history. In Jimmy Cobb's case, it was his participation in Miles Davis' LP "Kind of Blue," the best-selling and most influential jazz album of all time. Cobb could do whatever he wanted after his five years (1958-1963) in Miles Davis' band - and there were grandiose works, for example, with the singers Dinah Washington, Billie Holiday or Sarah Vaughan among them - but he will always remain one thing above all: the drummer on "Kind Of Blue". Since its release in 1959, the album has sold an average of 400 copies a day, making a total of six million units. In 2009, Cobb presented his brilliant Miles Davis tribute project at Enjoy Jazz. Beforehand, we met him for an interview.

(The interview was conducted in 2007)

Jimmy Cobb, you have taught yourself to play the drums mainly self-taught. self-taught. After a lifetime with your instrument, can you still remember your early fascination? can you still recall your early fascination?

Jimmy Cobb: Sure you do. This was in Washington, D.C. There was music playing nonstop in our neighborhood at the time. A lot of my friends had jazz records. And so we spent our time hanging out and listening to music. One of those people who got together there regularly was an amateur drummer named Walter Watkins. He used to drum to the music to the music, and that fascinated me. We knew mostly the big big bands at that time, the music of Tommy Dorsey or Gene Krupa, because it was they who had the big record contracts. Until a disc jockey from New York came along, who had all these bebop records in his luggage. Those were hard for us to get because the bebop artists could only release on small labels. We listened to these records we listened to them until six in the morning without a break. It was a very interesting time in Washington: lots of clubs and weekly changing, very renowned bands from Stan Kenton to Count Basie.

How did you actually get your first own drum set?

JC: Yes, the first drum kit. I bought that at some point and practiced using a book by Gene Krupa. The salesman at the time realized that I really wanted my own drum set more than anything else. So he suggested a fair price to me. I did not have the money but I didn't have the money, logically. So he asked me if I had a steady job, and I said yes. Then he offered me to gradually pay off the drums in weekly installments, because he saw how much it meant to me and that he could therefore rely on me. And that's how it happened. That's how I got my first drum kit.

A beautiful story.

JC: It was a good time for me. I had the opportunity at that time, during and immediately after the war, I had the opportunity to play with a lot of people that I would never have been able to get to otherwise. Because a whole bunch of good musicians were in the Army and therefore unavailable. For me, this offered unbelievable opportunities in the musically very attractive and lively and lively environment of my hometown.

With your participation on "Kind Of Blue" by Miles Davis you made yourself immortal as a musician early on. immortalized as a musician. Did you actually have the feeling back then that you were part of something special?

JC: Not at all. Even if it is difficult to understand today. You have to see it from the from the point of view of the time in order to understand it. The special thing was really the band itself, the interaction with these wonderful musicians, perhaps the best of their time, less the individual project. At that time, everything was happening so rapidly, there was movement everywhere, and you never knew whether what was new today would become big or whether tomorrow no one would be interested anymore, or whether tomorrow you might succeed in doing something even more exciting.

That means then: The special is not, it is made by the time, right?

JC: That's how you have to see it, at least in this case. In terms of the recording of "Kind Of Blue" we all just felt like it was a really good job and fun to play this stuff. It was a great time in the studio with everyone doing their best. But that's all it was from that point of view. I don't think for any of us.

After more than 50 years of living jazz history, after many years in the focus of the great, probably unrepeatable leaps in development, what still fascinates you about this music today?

JC: Very simple: music is what I do. Because I want to do it and because I think I'm good at it. Still am. And who knows where I would be today without music ...

You once said: "The drummer has to swing the band" - is that something like your personal credo? credo?

JC: Absolutely. A band that doesn't swing doesn't live. Making it swing is primarily the job of the rhythm section the job of the rhythm section and especially the drummer. That was the case from from the beginning, even in Dixieland jazz. Basically, it's a very simple thing. That's why it works and will always work. Provided you do the job sensibly.

Date: September 2, 2023