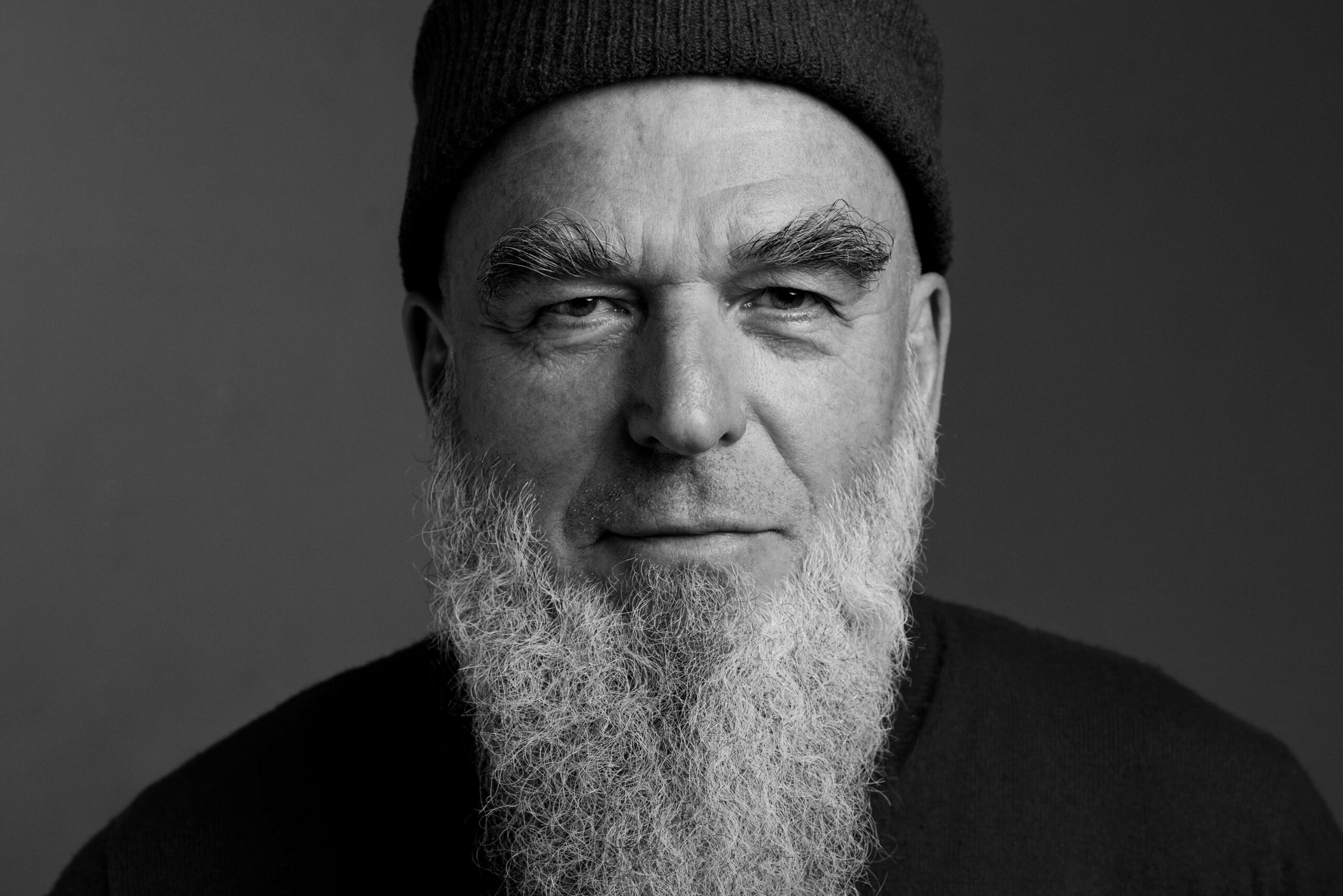

The understanding of drums has changed more than that of other instruments in recent decades. The days of pure time keeping are long gone. Modern drummers are less and less the foundation, they dispose the stones. Reduction is therefore one of the meta-trends. A particularly creative advocate of this movement and a true sound savant is Erwin Ditzner, for whom sometimes even a small drum is enough to build up a space-opening rhythmic universe. Festival director Rainer Kern found and still finds this so special that he gave Ditzner the Enjoy Jazz Festival's only white card, giving him free rein to create an annual festival concert. This has resulted in quite a few audiophile records with live recordings, including a highly exciting duo with pianist Chris Jarrett. (Interview from 2016)

Ditzner is largely self-taught. He broke off his classical training as a drummer after one year. His university teacher, with whom he is still in contact today, immediately recognized the problem and put it in a nutshell: "The thing with classical music and you somehow doesn't work. Because you want to groove permanently."

Nevertheless, the short time at the Wiesbaden Conservatory was helpful in that it established, for example, Ditzner's love of the snare drum mentioned at the beginning of this article, which continues to this day, and generally his preference for rudimentary equipment; the Worms native is a sound tinkerer in microcosm, he is attracted by the inner life of sounds. Here he searches for differentiation and variety. His meticulousness in dealing with the possibilities that lie in an instrument, always questioning himself, has almost become a trademark; the deep respect for each individual tone, which in turn contains an infinite variety of formulation possibilities. For Ditzner, the sound is therefore not created by the impact of the stick on a skin. It is already present as an idea much earlier, and its physical realization is not an isolated action, but the culmination of a process chain, which also includes empty spaces or unplayed tones.

The intensity of the rhythm is not technically generated, does not primarily have to do with rhythm and timing, but is pure or all-encompassing musicality. His playing, as if dramaturgically accomplished and, if necessary, sometimes strikingly pointed, always works with a kind of resonance that imperceptibly connects the tones of the other players in an airy way. Ditzner's playing carries without having to draw in a level of its own. What is produced here on the drum set is a kind of atomized sound. Core music. There is no longer a classical whole; only particles that not only communicate with each other, but with everything that makes up the respective present musical space. Ditzner's percussion work springs from listening, not from playing. This has a prehistory.

"I've always recorded myself. Everything I've played, I've recorded. I have stacks of music cassettes, DAT tapes, files at home. Listening to them, I often had the experience that my perception on stage had much less to do with the recording than I thought. My perception in playing was different than in listening. This led me to the realization that I probably tend to do too much on stage. So I ended up reducing my playing more and more. The advantage was that when I listened to the music, I could still remember how I felt when I played. Putting that into perspective holds enormous learning potential. Because a lot of what you think is good out of the moment doesn't end up serving the music at all."

But how does one approach the ideal of uncompromisingly music-serving percussion playing? One can understand this methodically very well by observing Ditzner on stage - he is very pragmatically inclined here. He has a kind of basic sound, carried by a very own style, in a certain way one could even call it a positive cliché, quite rich in variation, but which he always uses only at the beginning of a piece. On this basis he now begins to listen. He waits patiently until he has understood what his counterpart wants, what he offers, what idea he has in his head. Then a kind of corresponding scanning begins. Ditzner successively bases his sound on these ideas, checks and expands them if necessary, and intuitively searches for tonal congruence. This process can take seconds or even minutes. It requires the highest concentration and empathy. And because all this happens in playing, it naturally also means stress.

"Right."Ditzner confirms, shrugging his shoulders, "but there's no other way. At least with music that takes its time to develop quite organically in the style of a session. Of course, this approach makes no sense when I play in the theater, for example. There, you've already gone through everything in your mind beforehand and thought about how something could develop on stage and what role I should and would like to take in it. But the process is basically the same." The drummer has made a virtue out of necessity. He doesn't read music. "For that everyone knows," says Ditzner about Ditzner "he has ears. Sometimes the rehearsal may take a little longer, but something very unique often comes out of it."

What this does not allow is to deal with the sheet music only a week before a production and then play more or less flawlessly from the sheet. Ditzner sometimes invests a month or two in preparing larger projects. That may sound uneconomical, but he has become so well organized over the years that he can handle this extra work. He simply has to live with the material, he has to feel it around him and inside him, and above all he has to listen to it constantly: at home, in the car, in the rehearsal room, at almost every opportunity, until he has the music in his head and body.

"The advantage is"says Ditzner "that I am much more conscientious in my work today than I used to be. Twenty years ago, I didn't know this intensive kind of preparation. Back then, it would have been unthinkable, as it is today, to have committed to a workshop in July and to have already started thinking about it in February."

When asked whether this effort pays off economically, the drummer nods with a smile and refers to his schedule: "Sometimes it's almost too much. I was looking just now to see if I could find a 14-day corridor without commitments in the near future, so I could just sit on the train and not be available." Our conversation also took place with the caveat that he might have to cancel at short notice and go to France for recordings.

If Erwin Ditzner had one wish, he would first of all leave many things exactly as they are. as it is, especially the multitude of his current projects.

"But I would like to have the opportunity with each of these projects to work for three weeks at a time, to tour and let things develop. That's what I miss in this fast-moving business: consistency, continuity, time. Recently I was on the road with a German-Indian cast, first in India, then in Germany. It was totally fascinating to see what can develop in a very short time."

Ditzner, who also released a solo CD in 2013 with "Elements," is currently juggling with about ten different projects, from solo to large-scale, from cabaret to musette to modern jazz. This always involves different drumming and, of course, often a different setting:

"The number of projects is not the most exhausting thing, but their diversity. Last week I played on Wednesday in the theater or ballet, with 11-piece band and rock set, the next day I was with a small set at 'Jazz am Neckar', the day after the release concert of Cobody, where again rather a rich sound was required, dirty and funky and then the next day a gig with the Twintet, so with two horns, in a small hall in which I also made the sound while playing. When the week was over, I really patted myself on the back, which rarely happens."

One of Ditzner's outstanding CD projects is the duo's second album with saxophonist Lömsch Lehmann, one of Europe's best in his field. The two have known each other for about 25 years and, together with Sebastian Gramms, form a kind of small jazz family that appears in public in ever new constellations - but, strangely enough, almost never as a trio. The project with Lömsch is unquestionably a highlight in Ditzner's discography and sets standards in terms of reduction and fidelity to sound.

"The new duo record was created by simply cutting 70 percent of our output," Ditzner relates. "It was not about showing what is possible in terms of playing technique. We simply forbade ourselves quite a lot of things. We wanted a certain balance. No eruptive climaxes and outbursts, but clarity, density. We completely freed ourselves from standardized expectations. We didn't care if the jazz police would wave us through. The whole thing took two years."

The result is an album that is almost manic in its restraint. If you start out with the resolution that every note played must have a meaning, then you can, especially as a jazz musician, either panic in the face of the fear that you might run out of notes, or you can let yourself fall into an emptiness that leads you, perhaps not to completely new sounds, but to the only right ones in each case, to a symbol of musical sublimity. This is one of the best German duo recordings of the last ten years. The masterly and aesthetically transparent concept of an exclusively music serving play without virtuoso vanities is suitable to set standards. Here two great individualists have not only found a voice, above all they have something substantial to say with it.

Date: June 22, 2023